In the Netherlands banks have a duty of care for their own clients, and also for third parties who do not bank with them. Under this case law victims of fraud or scams can in certain cases claim damages from the perpetrator’s bank.

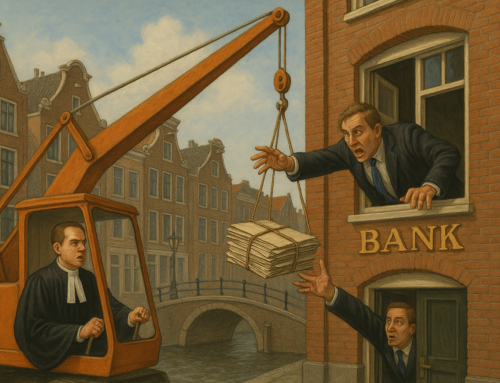

Banks’ duty of care

Under the Dutch civil legal system banks have a duty of care for their own clients, account holders and investors. Case law from the highest court, however, takes this duty of care further than the banks’ own clients. In certain cases third parties that are not clients of the bank can make a claim for damages if the duty of care for third parties is violated.

Duty of care for own clients

It is not surprising that banks in the Netherlands have a duty of care for their own clients. Comparable regulations apply in most countries. For instance, banks may only sell financial products that suit the client. They are required to know their clients. This requirement particularly applies to clients who want to invest. Free investment without advice from banks is permitted, but in the Netherlands a free investor must undergo a test to ensure sufficient knowledge of the investment process. If the bank invests on behalf of the client it is required to enquire whether the client is prepared to take the risk. Duty of care for clients is an integral element of contract law.

Duty of care for third parties

Third parties who believe that they have suffered loss as a result of the activities of a Dutch bank can hold the bank liable. Third parties cannot rely on the rules of the contractual relationship but must base their claim on the doctrine of a wrongful act. Under the Dutch Civil Code article 6:162 BW forms the legal basis for liability in non-contractual relationships. In the Safe Haven judgement of 23 December 2005 (NJ 2006/289) the highest court in the Netherlands, the “Hoge Raad”, recognised the duty of care of banks toward third parties. The Hoge Raad deemed that banks have a social function to serve not only their own clients but also society. A consequence of this social function is the existence of a special duty of care toward third parties who are not clients.

Open norm

Banks are required to take the reasonable interests of third parties into account on the basis of a so-called social decency norm or standard of normality, an “open norm” in Dutch law. In the case of an open norm the outcome of a possible court case is not easy to forecast. Every case is different, the judgement of the court depends upon all the facts and circumstances of the case. The Hoge Raad does name certain factors that play a role in the judgement. The norms of supervisory bodies such as the Central Bank, and regulations relating to financial products can play a role. Guidelines relating to prevention of money laundering and terrorism can also be taken into consideration.

Cases relating to duty of care

Subsequent to this decision in 2005, on several occasions it has been the case that third parties who are not clients of a bank have successfully claimed damages from a Dutch bank as a result of certain actions or omissions of the bank against them. In the Netherlands the banking world is dominated by three big banks: ING, ABN AMRO and Rabobank. There are also many smaller banks that together control approximately 20% of the market. The largest of these smaller banks are F. van Lanschot and SNS Bank. The big banks in particular, who handle the lion’s share of money transfers, have had to deal with “Safe Haven” procedures.

The decision of 2015

In 2015 the Hoge Raad again issued an important judgement (ECLI:NL:HR:2015:3399). The Hoge Raad gave a more detailed formulation of the duty of care: “The social function correlates with the fact that banks play a central role in the payment- and stock market traffic and related services, in those areas that are pre-eminently specialised and require possession of relevant information that others do not have. This function justifies that the duty of care of the bank also extends to protection against levity and lack of knowledge and is not limited to care for persons who are clients of the bank in a contractual relationship.” this description provides new starting points for victims of fraud and scams who wish to hold a bank liable for a lax attitude toward making payment facilities available to a fraudulent client.

A fraud in Hilversum

What was the actual case that led to this judgement? This case takes us back to events in the town of Hilversum, not far from Amsterdam. A company that attracts investment money from investors has an account at a branch of Fortis Bank, a predecessor of ABN AMRO. The income from the new investors is used to pay out to prior investors, a so-called “Ponzi swindle”. The bank is blamed on the ground that it could and should have recognised the fraudulent activities. The basic premise for that blame is that a bank must take timely measures to prevent damage to third parties and thus banks must keep an eye on movements in the accounts of their own clients. There is in these kinds of cases the problem that the victims who want to claim against the bank have an information deficit. If they act together they can map out what amounts have been deposited into the account of the fraudulent company, but it is very difficult, if not impossible, to obtain information about the outflow of money due to bank confidentiality, if the bank refuses to divulge any information. In this case however, the investors had managed to get a good picture of the way in which the fraudster had used the money on the account.

Information from the criminal procedure

In the first place, the fraudulent company had been declared bankrupt and the curator had in his report precisely set out how the fraudster had disposed of the money. Secondly, the fraudster was prosecuted by the Dutch Public Prosecutor. The documentation of the criminal procedure is confidential, but during the hearing important information on the course of events came to light. This enabled the defrauded investors to conclude that the bank should have taken action to prevent damage at a much earlier stage. If the bank had done so, there would have been no damage. There was thus a causal connection between the bank’s neglect and the damage suffered by the victims. Under Dutch law causal connection is required for a successful claim on grounds of an unlawful act, and this requirement was thus met.

The judgement of the Hoge Raad from 2015 makes it clear that banks in the Netherlands are obliged to monitor the payment traffic of their own clients and that, if necessary, they must intervene in the event of a reasonable suspicion of fraud.

Guidelines of the Central Bank

The Dutch Central Bank (De Nederlandsche Bank N.V.) has set rules for the manner in which this supervision should take place. These rules are not limited to the requirement to report transactions that could be connected to money laundering of the proceeds of crime or the financing of terrorism. They are also about the integrity of financial institutions in general. All forms of fraud and scams are undesirable and result in damage. Banks must refuse fraudulent clients and intervene in the payment process in order to prevent damage. Due to these developments banks in the Netherlands are not only forced to report suspicious transactions to the supervisory body but also to address the question of whether they should intervene in the payment process if third parties who are not their clients could become victims of fraud.

Transaction monitoring

The means to perform this supervision internally is transaction monitoring. Banks must construct a risk profile of existing clients, and also when taking on a new client. Transactions that do not fit that profile can be considered to be unusual and therefore reason for closer inspection or reporting to the supervisory body. The profiles are dynamic and must be adjusted from time to time because the income and capital of a client can change for a variety of reasons. The banks’ systems can generate an “alert” relating to an aberrant bank transaction that is subsequently assessed by a bank employee. In general, banks are now more vigilant and fraud and scams are spotted at a much earlier stage. This, however, takes nothing away from the fact that criminals and scammers are cunning and will always find new ways to fool the system and stay under the radar.

Procedures relating to the role of the bank as facilitator

Victims of scammers and fraudsters often get no redress from the perpetrators, who are masters in the art of making money disappear. Despite the improvements in monitoring transactions, thanks to new technical opportunities, procedures against banks due to breach of the duty of care for third parties are now a regular occurrence. Our office is currently handling several such cases. Sometimes it concerns a “boiler room”, a fake investment website that has succeeded in escaping the control systems of the bank. A bank can in all good faith provide a dubious company with an account that is then used for receipt and disposal of clients’ investment cash. Also with a view to the norms and guidelines of the Central Bank, it is expected of the bank that it recognises the fraudulent character of movements on the account and that it intervenes in order to prevent damage.

More examples of claims against banks

Other claims against banks concern, for instance, crooks who have taken large amounts of money from vulnerable elderly people for work on their homes that was not actually carried out or for which they issued vastly overpriced invoices. These payments can form an unusual transaction pattern given the normal payment traffic of these victims. It is not so that banks make no effort to look out for fraudsters who prey on elderly people, but sadly there are even so still cases in which the control systems fall short. If we, as specialists in these kinds of procedures, have a strong suspicion that the bank has fallen short in its duty of care for third parties, we can bring such cases to court. Not every case ends with a judgement from the court. Such matters are regularly settled between the parties, often with a confidentiality agreement.

Settlements with banks

Banks are reluctant to have business-sensitive information exposed in a public procedure, a fact that sometimes contributes to the bank’s preparedness to settle out of court. On the other hand, in some cases the court concludes that the bank has not breached the duty of care for third parties; every case is different and must be judged on its merits.

Own risk

In most cases the court does not require the bank to cover the entire damage. Article 6:101 BW of the Dutch Civil Code provides grounds for the court to apply a discount relating to personal responsibility or imprudence on the part of the victim of the fraud. A good example of this can be seen in the judgement of the Rechtbank Amsterdam of 26 July 2017 in the case Foot Locker vs. ING Bank N.V..

Foot Locker vs ING Bank

The facts of this case are as follows. A 25-year-old man registers a one-man business with the Chamber of Commerce. He opens a business account with ING. By means of invoicing fraud he manages to trick Foot Locker, a big company, out of almost € 2,000,000. The money disappears and the man is convicted. Foot Locker calls upon ING to compensate the damage due to breach of the duty of care on grounds of the Safe Haven jurisprudence. ING had no option but to defend itself in this procedure. ING itself apparently also found the transactions unusual. A report was submitted to FIU-Nederland, the body to which unusual transactions must be reported. A questionnaire was also sent to the account holder, who reacted with an excuse (vacation) and subsequently gave false answers (he said he was eligible for commission from Footlocker). The court blames ING for its lax approach. A call should have been made to the account holder to demand an explanation and the account should have been blocked in order to limit the damage, according to the judge in his summing-up. Thus, the court expects a more active policy from the bank.

The bank is not required to compensate the total damage due to culpability of the victim

ING is required to compensate the damage, with deduction of a percentage for victim culpability due to carelessness (art. 6:101 BW). The court justifies this with the argument that Foot Locker should have paid more critical attention when the fraudster announced that the account number had been changed. With such large amounts of money, the court expects from a professional company that checks are made in such circumstances. To that extent a reduction in the amount of damages to be paid is justified. And the criminal account holder of ING? Well, he has deftly made the money disappear, there’s nothing more to be had from him. Once he has served his time he can live a very comfortable life.

If you would like more information on this subject please contact our office.

Written by Marius Hupkes